Please choose how you would like to display prices.

You have no items in you shopping basket.

Checkout using your account

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Checkout as a new customer

Creating an account has many benefits:

- See order and shipping status

- Track order history

- Check out faster

Climate & Environment

The 'Conference of Parties' (COP) is the biggest global meeting regarding climate change. This is where every country in the UNFCCC meets to check their current progress and then set new targets in the fight against climate change. It happens once every year, with last year 2021 being the 26th.

The UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) is an agreement involving 197 countries, working to limit human interference in the climate.

For instance, COP3 resulted in the 'Kyoto Protocol', where countries signed a legal binding document that aimed to enforce the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, based on the scientific consensus that global warming is occurring and that human-made CO2 emissions are driving this phenomenon.

COP15 ended with disagreements between countries, however COP16 launched the Green Climate Fund, which is a fund handled by the UNFCCC to assist developing countries in adaptation and mitigation practices to counter climate change.

COP21 resulted in the 'Paris Agreement', while similar to the Kyoto Protocol, the major difference was that the Kyoto Protocol required only developed countries to reduce emissions, while the Paris Agreement recognized that climate change is a shared problem and called on all countries to set emissions targets. This required all countries to strengthen their climate change commitments every five years.

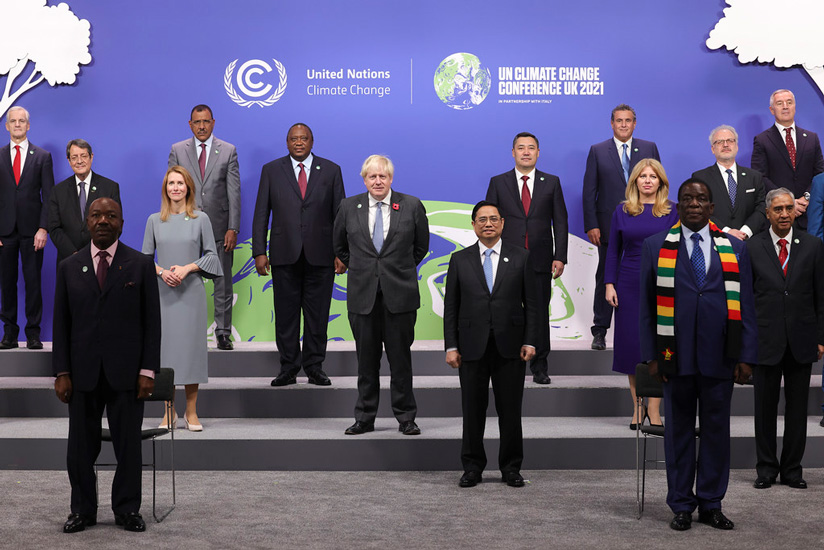

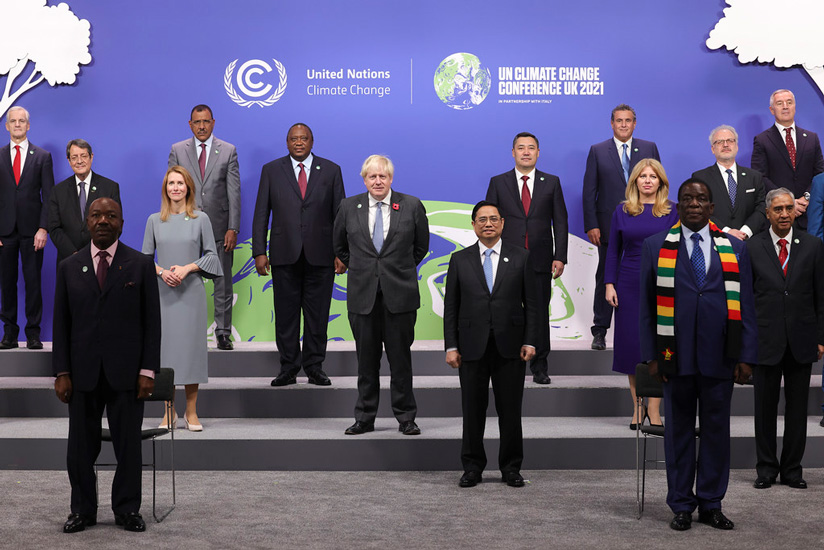

After being delayed a year due to COVID, COP26 was also the first meeting after the ‘IPCC’ (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report, which has been described as a "code red for humanity".

With COP26 taking place in Glasgow, a raft of commitments and deals were made in a bid to limit global warming and stop a climate change catastrophe.

How does this affect retailers?

The UN Fashion Industry Charter for Climate Action upgraded its commitments during COP26. This charter included signatures from 130 different brands - ranging from Primark and H&M, to Inditex and LVMH. Under this new Charter, all signatories agreed to set science-based targets by the end of 2023 or halve their emissions by 2030, and then reach zero emissions by 2050. As such, these fashion retailers now have 12 months (until 2022) to submit their plans to achieve the new targets - which will include elements such as switching energy in their supply chains to renewable sources, eliminating coal entirely, and ensuring that garments are made from net-positive materials.

Another element of the charter is that retailers will need to work with their suppliers to implement the changes. For example, coal must be phased out of tier one and two suppliers by 2030, including avoiding the use of any new coal power by 2023. Suppliers will need to put in place science-based targets to meet wider climate objectives by the end of 2025.

While this might seen quite far off, one real-world example that is already growing is the push for “Degrowth” - essentially, a growing movement that combats the capitalist idea of "continued growth at all cost". Such examples of degrowth would be the increase in "make do, and mend" mentality, the growing interest in vintage (this includes clothing from the 90s and early 00s), or the increase in apps such as Vinted. De-growth pushes the opposite of society’s current mind-set.

Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, the Co-op and Marks & Spencer have pledged to halve the environmental impact of the weekly shop by 2030. They made promises as part of COP26 to reduce carbon emissions, food waste, packaging, and deforestation connected to the food they produce. The chief executives of the food groups, which together serve more than half of UK food shoppers, said in a joint statement: “We recognise that a future without nature is a future without food. By 2030 we need to halt the loss of nature.” All five said they would set science-based targets to help limit global warming to under 1.5 degrees. Their efforts will be monitored by environmental organisation WWF.

Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Waitrose, the Co-op and Marks & Spencer have pledged to halve the environmental impact of the weekly shop by 2030. They made promises as part of COP26 to reduce carbon emissions, food waste, packaging, and deforestation connected to the food they produce. The chief executives of the food groups, which together serve more than half of UK food shoppers, said in a joint statement: “We recognise that a future without nature is a future without food. By 2030 we need to halt the loss of nature.” All five said they would set science-based targets to help limit global warming to under 1.5 degrees. Their efforts will be monitored by environmental organisation WWF.

More than 100 countries also signed up to end and reverse deforestation by 2030, which will mean a crackdown on deforestation related to the production of foodstuffs such as soya (an overwhelming majority of soy is grown for animal feed), cocoa and beef in countries such as Indonesia and Brazil, which are imported cheaply to Western countries. That could mean higher prices for groceries – costs that will either need to be absorbed by supermarkets or consumers - or could mean smaller portions of imported meat, or even less meat available in general. This goes hand-in-hand with the growing sentiment amongst the UK population of "shopping local" or "eating local".

It also touched on shipping, which one of the most polluting industries in the world but is the go-to for most international retail supply chains. Nine companies including Amazon, Inditex, Patagonia, Ikea and Unilever committed to only move cargo on ships using zero-carbon fuel by 2040. Cargo shipping produces one billion tonnes of pollution every year, equivalent to the whole of Germany, but there has so far been little effort to regulate and reduce emissions. Decarbonising the shipping industry could cost upwards of $2trn (£1.49trn) of investment in cleaner fuels, as well as the production of new ship designs. The switch to greener shipping would have a knock-on effect on a retailer’s own carbon footprint, reducing overall emissions.

While these examples may take some time to filter through the retail industry, it marks a shift in the norm that could guide future retailers’ strategies.

EN

EN